H E R M I T P R O J E C T S

IN DE EP, 2018

Sovay Berriman, Anouk Mercier, Ellen Wilkinson and Sarah Wilton

Curated by Natasha MacVoy and shown in her house

Artworks and ideas from the artists' studios, shown amongst the paraphernalia of domestic life, with an opening night meal for artists and friends.

Curated by Natasha MacVoy and shown in her house

Artworks and ideas from the artists' studios, shown amongst the paraphernalia of domestic life, with an opening night meal for artists and friends.

Sarah Wilton's Studio experiment, 2018, biscuit fired porcelain clay, 2 x 7.5 x 13 cm

Drawing by Anouk Mercier with artworks by Ellen Wilkinson and Sarah Wilton on the window sill

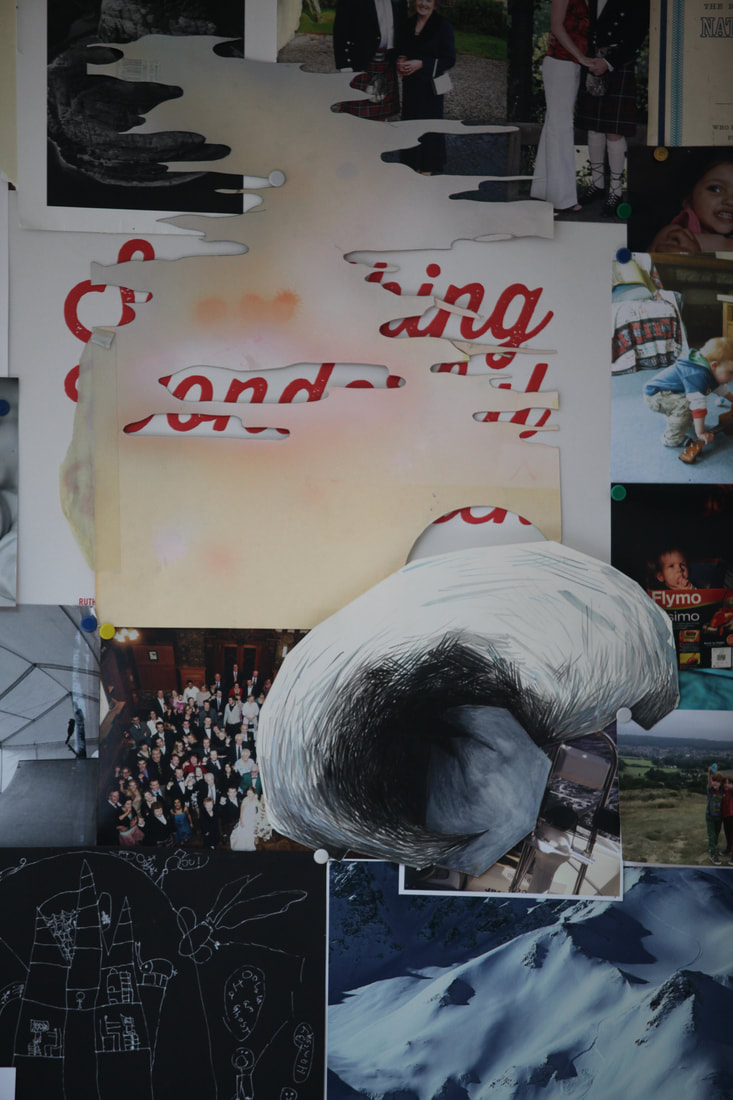

Artworks by Sovay Berriman and Anouk Mercier shown on the family memory board

Anouk Mercier (above) and Sovay Berriman (below) shown partially obscuring family photographs and drawings

The show became the backdrop for a meal between some of the artists and friends. During the meal the table cloth became a record of our conversation with notes, doodles, observations and comments bleeding together with the spillages and stains.

Following IN DE EP Ellen Wilkinson kindly sent an email with some thoughts about the show and the meal we shared:

Some thoughts on HER MIT

I sent my works to HER MIT in a shoebox: two- and three-dimensional experiments with materials, shape, form and colour that I had made to test ideas, not to be seen outside my studio. While I felt no need to explain these objects, to justify their existence, rough edges or lack of resolution, HER MIT’s domestic setting and intimate audience offered an environment in which they could exist and be tested against the real world.

While I felt completely comfortable with the idea of showing these sketched ideas in this context, the act of looking at my own and the other artists’ work in situ was surprising. I became aware of how little (at exhibition openings in particular) I look at and am expected to comment on the art. These primarily social events provide amble distraction from actually giving an opinion. In Natasha’s home, with works overlapping and competing with the stuff of domestic life, the need to look, think and ask why intensified.

Work was nestled between and on top of family photos, propped against a radiator, placed on a window ledge, blu-tacked to the fridge. I noticed other images. Some ‘art’, some ‘not art’: ceramics made by Natasha’s children were ‘equal’ to (better than?) their ‘art’ companions. Boundaries dissolved.

I didn’t notice everything at once. Some works made themselves apparent later in the evening, surprising me, though they’d been hiding in plain sight. These felt like a treat, a secret that had been shared with me. Sitting at the dining table, I looked at the drawings and prints in my immediate vision throughout the evening, the cumulative time I spent with them far greater than I would spend with an artwork in a gallery.

Earlier that afternoon we had walked in the woods behind Natasha’s house, enjoying the space, quiet and fresh air that our city home lacks. My partner received a call: his 92-year-old babcia was in hospital. There had been other recent hospital stays but this one felt final. Walking out of the woods and towards HER MIT we considered logistics: fly tonight? Tomorrow? Wait for further news? The possibility of regret?

During dinner we all drew and wrote, doodled and sketched our thoughts on Natasha’s tablecloth. We talked about making art, not making art, education, money, motivation, value. The guest who knew ‘nothing about art’ – of course – made the most astute observations. We talked about loss. We asked my partner again whether he wanted to go home or go to the airport.

HER MIT was a reminder of the importance of the people and things with which we surround ourselves daily. After all, living life and making art: isn’t it all just a work-in-progress?

– Ellen Wilkinson